Here’s what the Ghazal poetry form is:

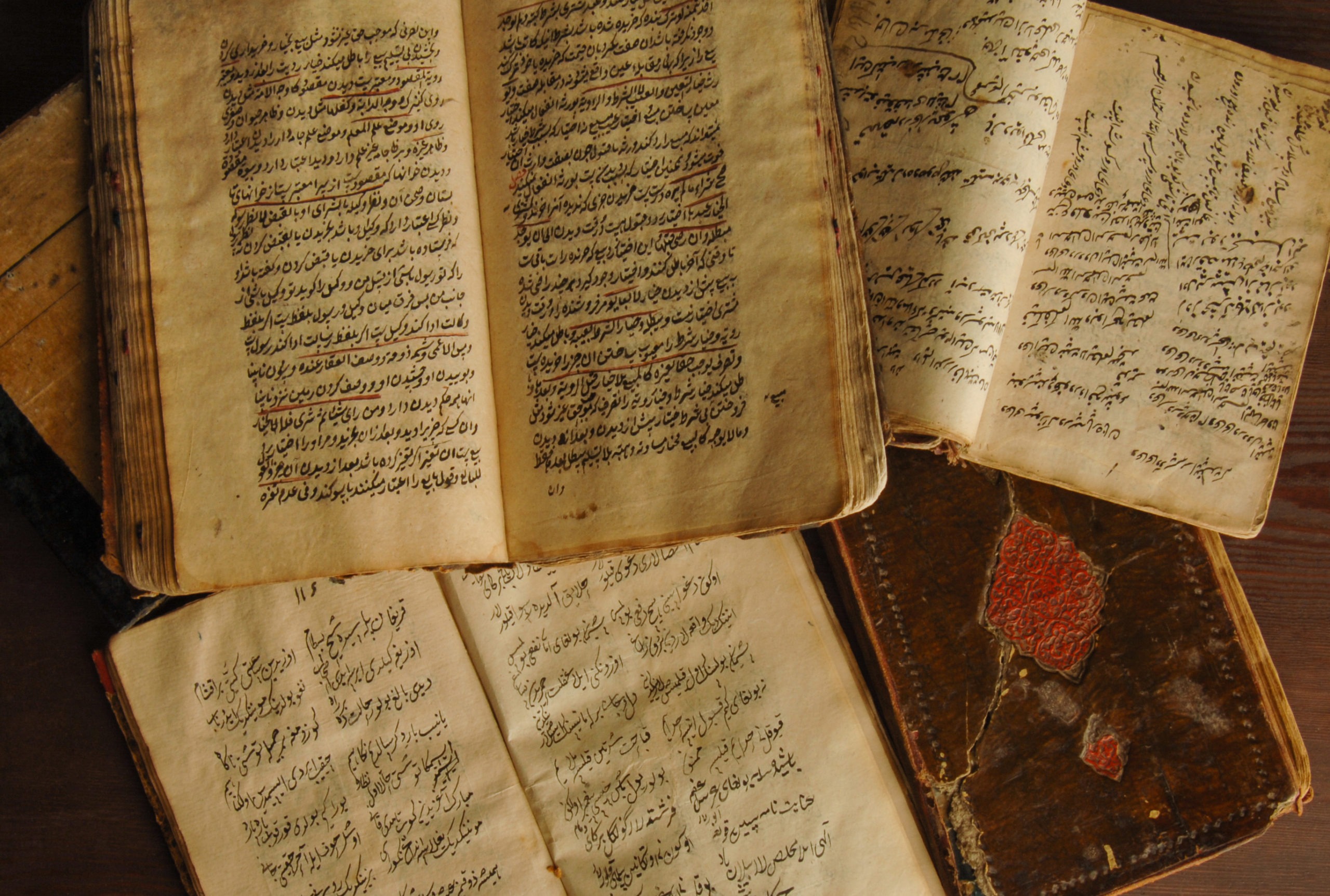

A ghazal poem is an ancient ode form of poetry that traces its roots to 7th-century Arabia.

The ghazal is usually made up of 5 to 15 independent yet linked couplets.

Ghazal poems are often expressions of the pain of separation, loss, and one-sided love.

So if you want to learn all about the Ghazal poetry type, then you’ve come to the right place.

Let’s jump right into it!

Forms of Poetry: The Ghazal

Ghazals are an ancient form of Arabic poetry.

There is a more bastardized version that is commonly used in English, but this article will also touch on the standards of the original for purposes of documentation.

Generally speaking, ghazals utilize a series of unconnected couplets that play with language and romantic themes, especially unrequited love.

Basic Properties of Ghazal Poetry

| Rhyme Structure | Yes |

| Meter | Metered in Arabic, usually not metered in English |

| Origin | 7th century Arabia |

| Popularity | Extremely popular in the Middle East and in some regions that experienced Islamic expansion |

| Theme | Most commonly about unrequited love |

How Are Ghazals Structured?

Ghazals are comprised of no fewer than five couplets and usually no more than fifteen (commonly between seven and twelve).

The first couplet, the matlaa, introduces the scheme that the rest of the ghazal will follow, utilizing a rhyme and a refrain.

The rest of the couplets will only borrow the refrain, otherwise acting independently of each other, though they will rhyme the second line with the original couplet.

As such the rhyme scheme of a ghazal will be AA BA CA DA EA, etc.

The refrain is unique in that is a word or phrase.

It is, by necessity, never an entire line and is instead only the very end of the second line in every couplet.

In Arabic poetry, all couplets are expected to mimic the meter of the matlaa.

This is usually considered optional in English interpretations of the form, though syllable count is often used mechanically as a stand-in.

The final couplet typically includes a signature and may specifically offer an interpretation of the poet’s name, though this last part is optional.

One of the most unique elements of the ghazal is that each couplet is autonomous and functions alone as a thought.

Ghazals traditionally explore deep questions, especially about love and longing.

Unrequited love is an especially common theme of ghazals.

This love is usually portrayed as unconditional and inexhaustible.

The speaker may even acknowledge in the ghazal that their love is hopeless but still insist on holding onto their feelings anyway.

Example of a Ghazal

Your eyes are the stars that dot my shining sky tonight.

Your lips, the subtle bliss of learning to fly tonight.

I see you in moonlight and stare like a fool,

unwilling to ask your secrets, to pry tonight.

All the things I cannot say well up over time.

You are both my despair and my high, tonight.

Yet you remain the treasure of a thousand nations,

with which a better man could surely buy tonight.

Oh but gather yourself up, Peter! Such beauty stings,

but I would gladly make this evening my tonight.

It should be noted that the above ghazal only follows the much looser and more forgiving standards of the English variant of the ghazal, but it should give a rough idea of what a ghazal is ultimately supposed to look like.

In this case, the ending word is “tonight” which is then repeated, naturally, on both lines of the first couplet and on the second line of every couplet afterward.

Meanwhile, the rhymes of the first couplet are “sky” and “fly.”

Thus the word appearing before tonight in every couplet must rhyme with these two.

This staggered internal rhyme is one of the most unusual qualities of the ghazal, at least to English speakers.

Since it’s so unlike more familiar forms that usually only address or emphasize rhyme on the very last word of a line (or within a single line).

History of the Ghazal

The ghazal got its start in 7th century Arabia, evolving from the much older and longer qasida.

This older form, consisting of up to 100 couplets, traditionally featured an opening prelude.

This prelude eventually became a separate piece on its own, which evolved into what we know now as the ghazal.

It should be noted that this is not unlike the history of the haiku, a Japanese form that traces its origins to a humble beginning as the first part of a longer renga.

There are French forms that similarly derive from older forms in this way.

This serves as evidence that poetry tends to evolve through similar mechanisms across cultures.

The Arabic ghazal inherited the entirety of its form from its origins in the qasida, especially in its usage of an end rhyme and refrain on every couplet.

Whereas the qasida tended to favor lengthy, difficult meters, the ghazal evolved to embrace lighter meters that were more appropriate to musical presentation.

The ghazal thematically also slowly changed from nostalgia for one’s homeland to romantic and even sexual themes that appeal to a wide audience.

The ghazal’s spread can be attributed to the spread of Islam.

The gradual spread of the Arabic language into Europe, Africa, and Asia brought with it Arabian poetry, including the ghazal, since it just happened to be a popular form at the time.

It was the Persian variant of the ghazal, starting in the 10th century, that continued to develop the form.

Persian ghazals made the matlaa more formulaic, enforcing the common rhyme across both its lines.

They also moved away from the enjambment that had been used up to this point, tightening the couplets into two mostly separate lines.

This was also around the time that the qasida fell out of favor.

The brevity of the ghazal, as well as the minor evolutions it had gone through, ultimately proved to give it more endurance than its parent form.

The English version of the ghazal was not finally recognized until late in the 20th century, near the turn of the millennium.

Many poets up to this point had made attempts to carry the form into English but it wasn’t until the serious efforts of poets like John Hollander and Agha Shaid Ali that the form started to gain some traction.

Tips for Writing a Ghazal

Focus your attention entirely on the end word and the preceding rhyme in your first few attempts and start short, with just five or six couplets at most.

Keeping the rhyme and refrain going will be significantly harder than you might expect.

So I do not advise trying to match your line lengths and/or meter initially, though it might be an impressive flex for later drafts.

When you first get to the word or syllable(s) that you want to use as the rhyme, just before the refrain, pause for a moment and write out a list of words that rhyme with it. (Or use a search engine to quickly find a list.)

This will accomplish two important things.

First, you will have a list to fall back on when you’re mid-line and trying to find a good phrase to work toward.

Second, you will have some initial idea of the difficulty of that particular word, syllable, or phrase.

If you find that it has very few rhymes, you may want to rewrite the first line so that you have something easier to work with.

As for the refrain, try to choose a word or phrase that won’t get too taxing when repeatedly written and read.

Readers are going to stumble less over a word like “now” than they would over something as oddly specific as “aardvark.”

In general, you should always be writing toward the next rhyme and refrain, even at the beginning of each couplet.

Writing out the full couplet, only to discover that there’s simply no meaningful way for it to end on the refrain, would be frustrating.

Poet’s Note

Ah, my old archenemy. I don’t like repetition, especially in poems, so this article caused me physical pain.

Ghazal is a beautiful word, though. No matter how many times you say it, it always has that exotic new word smell.

Comprehensive Collection of Poetry Forms: Craft Words Into Art

Dare to traverse the entire spectrum of poetic forms, from the commonplace to the extraordinary?

Venture from the quintessential Sonnet to the elusive Mistress Bradstreet stanza, right through to the daunting complexity of Cro Cumaisc Etir Casbairdni Ocus Lethrannaigecht.

For those with a zeal to encounter the full breadth of poetry’s forms, this invitation is yours.

Start exploring the vast universe of poetic ingenuity with our comprehensive array of poetry forms right now!