Here’s what the Jintishi poetry form is:

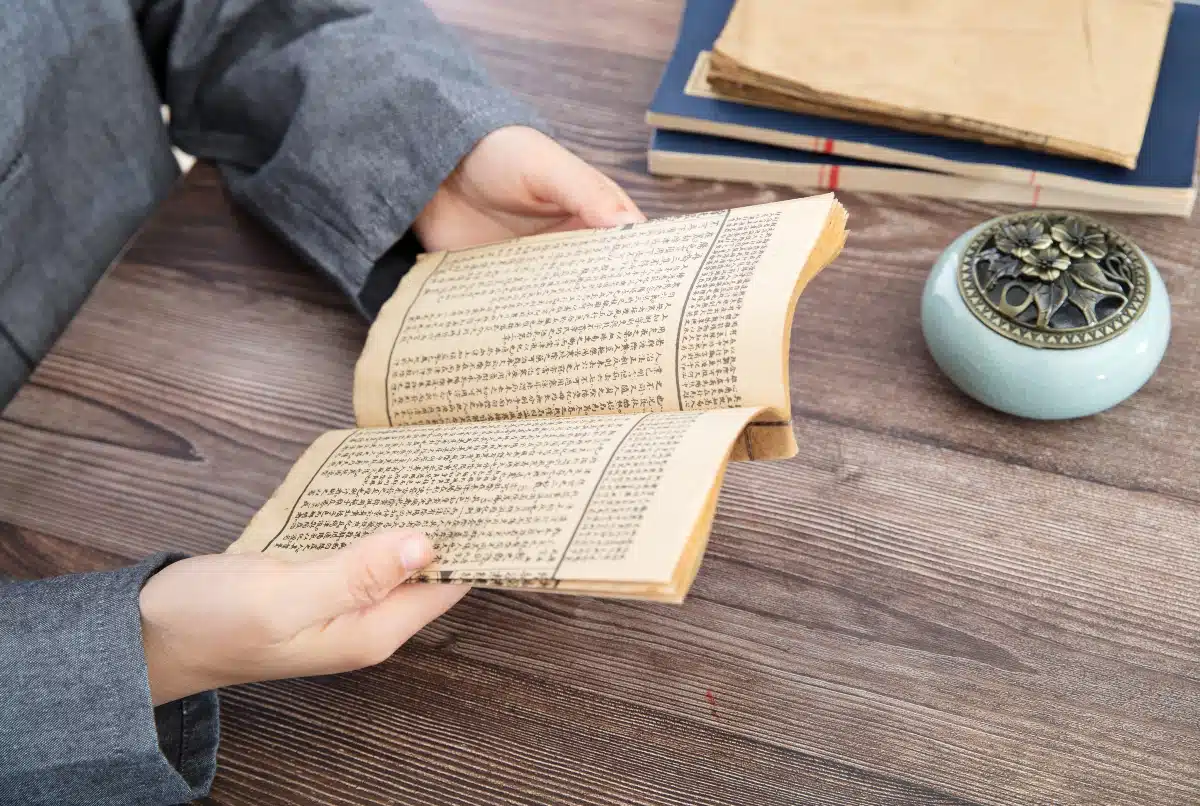

Jintishi, or regulated verse, is a group of Chinese poem forms that rely heavily on tonality and rhyme, traditionally written in couplets.

Sadly, this particular form is so entrenched in tonality that there is no true English equivalent, since the English language has a limited relationship with tone compared to Chinese.

So if you want to learn all about the Jintishi poetry type, then you’ve come to the right place.

Let’s dig deeper into it!

Types of Poetry: Jintishi

Jintishi, otherwise known as regulated verse, is a Chinese poem form that emerged around the 5th century, typically having its origin traced to Shen Yue and his “four tones and eight deflects” theory regarding tonality.

This form of poetry is unique to Chinese in that it relies heavily on tonality, a language trait rarely touched upon in other languages.

As a result of this, there is no such thing as a true “English Jintishi.”

While many foreign forms can be translated into English by making several concessions in their structure and specifics, the tonality of Jintishi is central to the form and is a non-negotiable property.

Since there’s no obvious English equivalent, it should be understood that the form loses too much in translation to be truly comparable.

Basic Properties of the Jintishi

| Rhyme Structure | Varies; relates to tone |

| Meter | Based on character count |

| Origin | China |

| Popularity | Most famous in the Tang Dynasty; restricted to China |

| Theme | Varies |

The History of Jintishi

Shen Yue (441-513 AD) is usually credited as the original mind behind Jintishi, even though Jintishi is often regarded as a form of the Tang Dynasty which did not come into being until centuries later.

Shen Yue, whose courtesy name was Xiuwen, was a famous poet, historian, theorist, and politician who served under multiple emperors.

It was his theory of tones that set the groundwork for Jintishi, though the form’s proper introduction into poetry seems to have come a bit later.

Some of the biggest contributors to Jintishi were Shen Quanqi, Song Zhiwen, and Du Fu, all of the Tang Dynasty.

Du Fu, in particular, is frequently called the greatest Chinese poet.

How is Jintishi Structured?

Jintishi are always arranged into couplets.

The total number of lines will be four for jueju, eight for lushi, and ten or more for pailu.

Lines are expected to have the same number of characters.

Usually five or seven, though there are surviving examples of Jintishi with seven characters per line.

Note that a “character” does not refer to a letter in the sense that English speakers understand the term.

The Chinese written language is famously very different in that regard, so it would be more accurate (but still an over-simplification) to compare these measures to syllable counts.

Rhyme (also known as rime in this context) is mandatory and may be based on formal rhymes from a “rime table.”

This is also where the first problem with translating Jintishi crops up.

Generally speaking a Chinese Jintishi would rhyme level tones with each other and non-level tones with each other, but English speakers would struggle to understand the difference between level and non-level tones since our language does not employ tonality in the same way.

There is also a fixed pattern of tonality alternating deflected and level tones.

Importantly the popular four tone system created to describe Middle Chinese makes this distinction clear-cut.

Parallelism is employed.

This might involve contrasting lines against each other, mirroring grammatical structure, etc.

The bottom line is that the couplets are expected to be parallels of each other in some meaningful way.

The short jueju tends to be the most flexible.

Caesuras are also expected at regular intervals, with their placement shifting depending on the lengths of the lines and verses.

Poet’s Note

This would normally be the part where I include an example and tips for writing the form, but that would be unrealistic in this case.

There are NO accurate Jintishi in English due to the constraints and using a translated Chinese Jintishi would be disingenuous since it wouldn’t showcase the tonality these forms are famous for.

As disheartening as it may be to hear, my only tip for writing Jintishi would be to learn Chinese.

There’s no shortcut.

And no, using stressed and unstressed syllables as stand-ins for tones will not have the same impact, in case you were wondering.

If you truly want to appreciate and master this particular form, your only option is to become fluent in Chinese.

Otherwise, you’ll just have to appreciate this one from a distance.

Comprehensive Collection of Poetry Forms: Craft Words Into Art

Dare to traverse the entire spectrum of poetic forms, from the commonplace to the extraordinary?

Venture from the quintessential Sonnet to the elusive Mistress Bradstreet stanza, right through to the daunting complexity of Cro Cumaisc Etir Casbairdni Ocus Lethrannaigecht.

For those with a zeal to encounter the full breadth of poetry’s forms, this invitation is yours.

Start exploring the vast universe of poetic ingenuity with our comprehensive array of poetry forms right now!