Here’s what the Tanka poetry form is:

A tanka is a short Japanese free verse consisting of 31 syllables.

While they don’t necessarily rhyme, tankas follow a specific syllable pattern.

Tanka literally means “short poem or song”, with themes that are usually about nature, seasons, and desires.

Hence, tankas tend to evoke strong and powerful imagery.

So if you want to learn all about the Tanka poetry type, then you’ve come to the right place.

Keep reading!

Forms of Poetry: Tanka

Tankas are a genre of Japanese poetry.

The main takeaway is that tankas are short poems, following a particular structuring of units, that have enjoyed profound popularity throughout Japanese history.

Although, the terminology has shifted and evolved across different eras.

Basic Properties of the Tanka

| Rhyme Structure | None |

| Meter | None, utilizes Japanese on instead |

| Origin | Japan |

| Popularity | Consistent popularity across Japanese history |

| Theme | Varies; traditionally about feelings, nature, or seasons |

How Are Tankas Structured?

In order to answer this question, we must first discuss on.

In English, we divide our poems into units such as syllables and feet.

Japanese poetry has a similar but distinctly different system utilizing phonetic units called on.

There is, unfortunately, no exact English equivalent to this unit and there are times when an on consists of more than one syllable.

For our purposes, however, it will be easier for you to understand if you remind yourself that wherever it’s mentioned is at least roughly equivalent to our English syllable as a unit of measurement.

That is coincidentally why we use syllable counts in haikus (which would also rely on units of on in the original Japanese.)

A tanka is written with a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. Each of these numbers references the number of on in a given line.

While we typically treat each of these units as lines when translated, it should be mentioned that this is more a preference of the translators than of the original text.

The first three units (5-7-5) are called the upper phrase, the kami-no-ku, and the last two units (7-7) are the lower phrase, the shimo-no-ku.

Fans of the haiku will notice that the upper phrase just happens to represent a haiku. This is not a coincidence, as you might expect.

Japanese formal poems are deeply interwoven with each other, frequently splitting from each other into new forms throughout Japanese history.

The haiku is an evolution of the hokku which itself branched off from the renga and so on.

Modern tanka and haiku share common ancestors and as such portions of old structures have spilled over into both.

The third unit of the tanka contains a pivotal image acting much like the turn in a sonnet.

From there, the lower phrase then takes the poem in a new direction.

History of Tanka

The term “tanka” was originally a way to distinguish a short poem from the longer chōka.

It was around the 9th century AD that the term experienced a temporary retirement as the new term waka was used to describe short poems, which were growing in popularity at the time.

The term was not properly revived until the early 20th century by the famous Masaoka Shiki, who advocated for a new age of short poetry.

It was coincidentally also Shiki who coined the term “haiku” to replace the previously accepted hokku.

This happened during the Japanese Meiji period, a period of history in which Japan was modernizing rapidly following both foreign and domestic influences.

Shiki was among the first to argue that Japanese poetry should be pressured to modernize, though a part of his influence was dedicated to bringing short poems back to what he saw as their “manly” roots.

The distinction between the terms waka and tanka is largely superficial and their history is intrinsically linked, as they largely represent the same general idea of “the short form.”

Waka regarding romance has been especially popular historically, as is typical of many poetic forms.

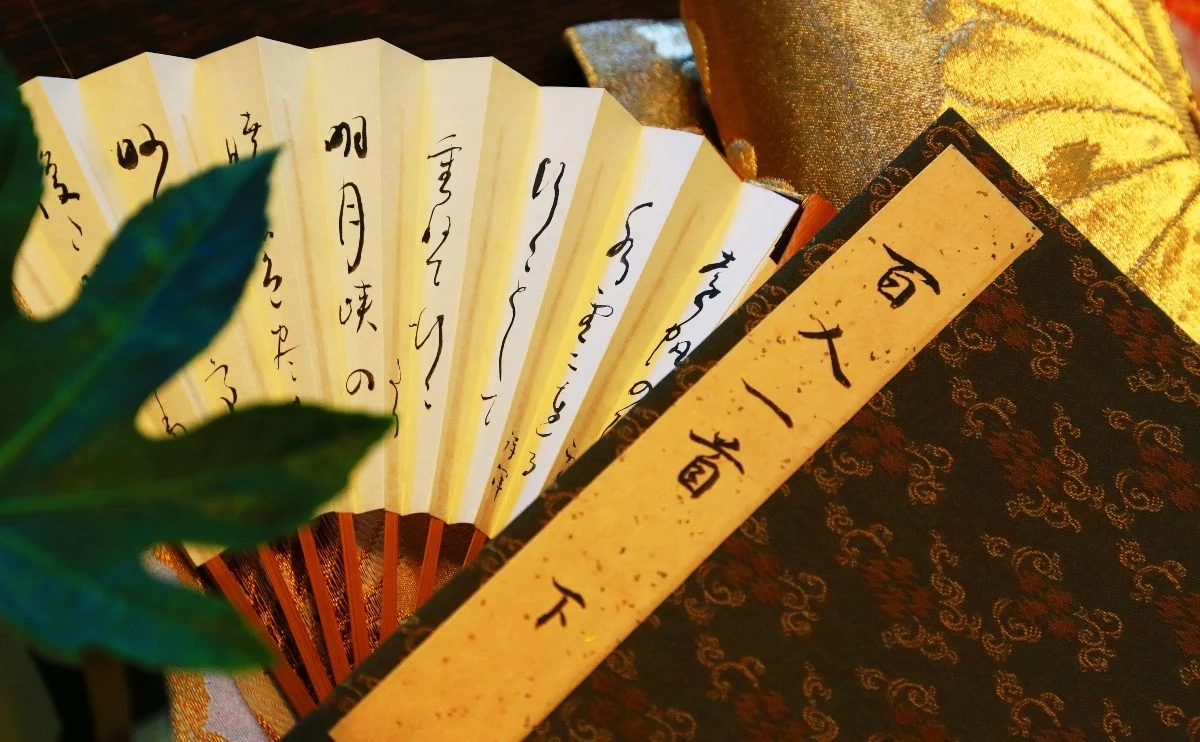

One interesting note about waka is that they were routinely used as replacements for letters between lovers or between writers.

It was considered more romantic to write a waka to a love interest than to write a standard prose letter, leading to a very different dating scene in which talented poets had a unique advantage over their peers.

Waka was popular enough to incite contests, parties, and social events. Their prevalence, as well as the high status of poetry in Japanese culture, contributed greatly to the conventions of Japanese society and literature through their sheer omnipresence.

The English Tanka

While the true form of the tanka simply doesn’t translate properly to English, there have nonetheless been numerous attempts at replicating the form’s unique charm in the west.

Like with the haiku, most practitioners agree that syllables are a suitable replacement for the Japanese, as no other unit seems to be closer.

The general convention is to write the five units of the tanka as five separate lines, but there are also writers who prefer to write a tanka as a single long uninterrupted line.

In both cases, an English tanka will end up with a total of 31 syllables to mirror the 31 in the Japanese tanka.

Writing a tanka in English is functionally similar to writing a haiku, then adding two additional lines/units that take the poem in a new direction. Below is an example of an English tanka:

Soft snow falls outside

whispering like new footsteps

on a hard window

mocking the silence of night

with its still blankets of frost

The lack of punctuation and the use of a single sentence is traditional but not necessarily mandatory.

The English tanka is inherently a bastardized form itself, so there’s no reason not to experiment with it.

Note that rhyme is typically not used and meter is of no use to a tanka due to the syllable counts.

In particular, take note of how the poem starts with the word “soft” and then uses the antonym “hard” to signify the moment that the poem turns from upper to lower phrase.

This “hard window” is a very blatant interpretation of the pivotal image, which should help with understanding the general idea.

Tips for Writing an English Tanka

First and foremost, abandon all hope of being completely faithful to the Japanese tanka.

The only way to write a tanka that is truly faithful to the standards and history of the form would be to learn Japanese.

Master the usage of it and become fluent enough in the language to understand an entirely different culture’s conceptualization of poetry.

Then start reading articles like this one, but in Japanese.

That’s not a realistic goal for most poets.

That said, the relatively new tradition of English tanka should be fairly easy for you to break into, given some practice.

Like the more popular haiku, this form does not come with the strict requirements of many forms native to English that employ meter and rhyme schemes and is instead more about capturing the tone and feel of a tanka.

If you would like to really capture the vibe of the tanka, as it is understood in English, then the best starting point would be with experience in reading the tanka of others.

Look for examples online, in workshops, and in communities that practice tanka regularly.

In general, a tanka is a form that is meant to be emotional and deep.

Still, it’s easier to get that understanding from reading poems and internalizing the style naturally than it is to mimic their techniques.

Tanka represents an interesting workspace where you will not be measured based on your technical prowess, but on your ability to portray an emotion or image with sincerity and conviction.

Write a tanka as an intimate poem, as if it were meant to be a secret between you and the reader, an understanding that you desperately want to share.

Above all else, a tanka is a test of your ability to see beauty in the world around you and to showcase your love of that beauty.

Whether you see that beauty in a tree, the pouring rain, or the curves of another person, a tanka is a place to pour those thoughts and feelings onto the page.

Poet’s Note

Japanese poem forms are always a bit confusing to research since they’re so deeply interwoven with each other.

It seems like every Japanese form has a parent form, a sister form, an older word for the form that’s no longer in use, and a few family pets. It’s a lot to keep up with.

Comprehensive Collection of Poetry Forms: Craft Words Into Art

Dare to traverse the entire spectrum of poetic forms, from the commonplace to the extraordinary?

Venture from the quintessential Sonnet to the elusive Mistress Bradstreet stanza, right through to the daunting complexity of Cro Cumaisc Etir Casbairdni Ocus Lethrannaigecht.

For those with a zeal to encounter the full breadth of poetry’s forms, this invitation is yours.

Start exploring the vast universe of poetic ingenuity with our comprehensive array of poetry forms right now!